For those of you who don't know, our previous blogger/researcher/page manager is a bit busy with, well, life. That's how she put it anyhow, I'm not sure how much she wishes to tell, so I'll keep my mouth shut.

Anyhow, I'm going to start off things in a manner a bit, how do I say, overly ambitious.

Yes, that's how I'll describe this project.

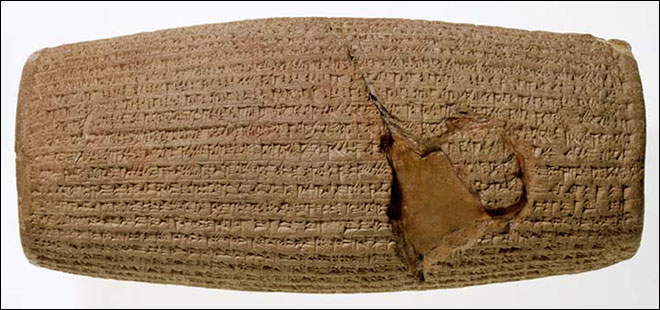

As those of you who already follow our page may know, the Cyrus Cylinder is arriving in Los Angeles to be on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum this Autumn.

The Cyrus Cylinder, image via

Now, this really is a special occasion. And as such, I think it deserves a special dress. Heck, I deserve a special dress, especially since I'm named after a character in Xenophon's Cyropaedia.

So what better way to honor this occasion then to dress up as the woman I'm named for? It also falls under the Historical Sew Fortnightly Challenge's Challenge #12: Pretty Pretty Princesses. (Though her historical existence is a bit questionable, but it is likely she, to an extent, existed in some form, though perhaps not entirely as the story depicts her, and definitely not with that Greek name they plastered on her.)

Let's start off with some of the relayed research. (I'm just blogging and costuming... I do have a job outside of here, so the research I'm still leaving to our other blogger, and boy, did she research!)

The Lady of Susa, Pantheia (alt. spelled Panthea/Pantea), wife of King* Abradates was a Susian woman married to an Assyrian king*. She was captured, after a battle, by the Persian and Median army and saved to be given to Cyrus as part of the spoils of war.

*King is literally what's used to describe him in the Cyropaedia, though he appears to be more of a Viceroy. I could get into this more, but I don't think anyone wants to read an essay that connects all the dots and closes up the gaps in the story. You're here for the costuming, I'm sure.

Supposedly, Pantheia is the most beautiful woman in Asia (Asia in the sense of this translation must most certainly mean all of Asia Minor, the Middle-East, and South and Central Asia, as I'm not certain of the Greeks knowledge/education on the farther reaches of Asia at this point in history) . But Cyrus, rather than take her as his own, decided instead to save her for her husband, as Abradates was still alive, and so, in Cyrus' view, her marriage to him was still valid.

And now here is her description from the Cyropaedia as her caretaker Araspes describes:

And then Cyrus called to his side Araspas the Mede, who had been his comrade in boyhood. It was he to whom Cyrus gave the Median cloak he was wearing when he went back to Persia from his grandfather's court. Now he summoned him, and asked him to take care of the tent and the lady from Susa. She was the wife of Abradatas, a Susian, and when the Assyrian army was captured it happened that her husband was away: his master had sent him on an embassy to Bactria to conclude an alliance there, for he was the friend and host of the Bactrian king. And now Cyrus asked Araspas to guard the captive lady until her husband could take her back himself. To that Araspas replied, "Have you seen the lady whom you bid me guard?"

"No, indeed," said Cyrus, "certainly I have not."

"But I have," rejoined the other, "I saw here when we chose her for you. When we came into the tent, we did not make her out at first, for she was seated on the ground with all her maidens round her, and she was clad in the same attire as her slaves, but when we looked at them all to discover the mistress, we soon saw that one outshone the others, although she was veiled and kept her eyes on the ground. And when we bade her rise, all her women rose with her, and then we saw that she was marked out from them all by her height, and her noble bearing, and her grace, and the beauty that shone through her mean apparel. And, under her veil, we could see the big tear-drops trickling down her garments to her feet. At that sight the eldest of us said, 'Take comfort, lady, we know that your husband was beautiful and brave, but we have chosen you a man to-day who is no whit inferior to him in face or form or mind or power; Cyrus, we believe, is more to be admired than any soul on earth, and you shall be his from this day forward.' But when the lady heard that, she rent the veil that covered her head and gave a pitiful cry, while her maidens lifted up their voice and wept with their mistress. And thus we could see her face, and her neck, and her arms, and I tell you, Cyrus," he added, "I myself, and all who looked on her, felt that there never was, and never had been, in broad Asia a mortal woman half so fair as she. Nay, but you must see her for yourself."

So she is a Susian, with the Assyrian army, and her husband was an Assyrian Viceroy type of person.

This actually tells us more about her real costume than the description does. But the description does offer a few insights. Despite the fact that she is Susian, the mention of the veil does imply that, as Abradates wife, she does abide by Assyrian veil laws. Or, on the opposite end of the spectrum, that Xenophon, a Greek, did not understand the veil laws and assumed it to be an attire worn by women of all stations.

Yes, veils and laws regarding them extend back even before Islam. Actually, veil laws back then were more of a prohibition against people who ought to not wear them. Yes, some women were banned from wearing veils because of their station in life.

In fact, with this detail in mind, it would seem that for her to be dressed as a slave, she would have had to be missing the veil. Or perhaps Susians had their own set of veil customs that have been lost to time (or that we here have been unable to find at least).

But this is a story about a Queen by someone of a different culture, written a century after the fact, and done in a poetic way meant to create a story. The veil is now acceptable slave garb because it makes a greater statement to have her tear it off later on and expose her real beauty, her hair, her face, her neck, her arms....

Wait, her arms?

Yes.

To understand this more, we must look at what women wore in what would be known as the Achaemenid era.

Women holding court on a seal, via

And in case it's a bit hard to see that, here's a line drawing:

Line Drawing via

Notice the sleeves.

Like their male counterparts, women wore robes with loose, flowing sleeves. Throw yourself to the floor in grief and mourn the way the ancients used to, and you will most definitely expose your arms to anyone, regardless of whether you wear the full, double-sleeved garments we associate with the Achaemenids, or the "single" sleeved garments of the Elamites. So it is very likely that Susa, who was the capital of the former Elamite Empire, and once ruled over Anshan, the place where Cyrus' father ruled over, wore these robes as well.

What should also catch your attention here besides the robes is the enthroned woman on the left.

She is who we will be copying.

She fits our description almost "to a T" (Sorry, I just learned that phrase, and I really like it). She is clearly the woman of highest rank in the image. She wears a crown, she wears the robes, and she has the veil. Yes, the woman on the right may also have one, but it's not nearly as large and encompassing as the enthroned woman's.

Now for colors, we have it pretty simple. It's not only actually well known what expensive and consequently "desirable" dyes were available in the ancient world, but thanks to Darius I, we have the colors of the most elite fighting force in the Persian Empire immortalized in stone.

Yes, the guards depicted at the at the palace of Darius I in Susa are wearing purple and saffron.

And if they could wear the two most expensive colors in the ancient world, so too, could a queen.

The Immortal Guard, from the Winter Palace at Susa, via

So we have our colors, our design, our components.... And materials?

Well, linen would be the obvious choice. And it will make its way into the gown most certainly. But what about an ancient commodity that the ancient Middle-East was known by?

Silk was/is not produced in Iran. But it's been produced in China as early as 2,000 BCE. It was traded extensively from China to the West via the "Silk Road" (this trade route is much older than some would have you believe) which ran directly through ancient Persia.

Of course, this being the case, it'd be odd if silk itself wasn't also extensively traded within the Persian and neighboring Empires. In fact, though it's a bit past our target date, there is recorded evidence of this purple silk hoarding by Persian royals in the Palace of Darius I in Susa.

And for pretty reference, supposedly, this is a silk cloth, dyed in purple, from the Achaemenid era.

The site says it was originally a garment, but then re-purposed as a saddle-cloth and buried with its owner.

Now, I am not going to make murex dyed cloth, It's too difficult, it's too expensive, and it's too questionable. So I will be approximating it, but I will be dying with saffron, real Persian saffron, because that is something I can do fairly easily.

And here is a rough sketch of what to expect (minus the veil, since it obstructs the design of the rest of the garment). The yellow fabric will be linen dyed with saffron, the purple will be silk, the white lines along the sleeves, belt, and hem are silk ribbon, which will hopefully be embroidered.in a geometric pattern later on.

And yes, I will be making shoes. I found a pair in Egypt that, while boots, not shoes, depict an eerily similar construction and wear method as indicated in Persian statues of the time.

Now I'm sure earlier the quote from Xenophon undoubtedly brought up the thought "But she was dressed in slave's attire. Why are you making royal clothes?"

Well because if you read the whole story, you understand that the slave's attire is to hide her form the Medes and Persians in hopes that they do not recognize her for her royal bearing. It's a popular story theme, and historical theme too I suppose, that to save the Queen or Princess or what have you from the clutches of the invaders/conquerors/people that might harm her you do it by dressing her up as a less important woman, and in some cases, dressing one of the slaves or servants up in her place.

But since she's instantly recognized for who she is, and she remains in captivity for quite some time, there was no longer any reason after the initial meeting for her to continue wearing the slave's attire. Certainly it would not have been comfortable for her, if she was a lady of such breeding even veiling herself couldn't hide it, it is likely that the rough linens and wools afforded to slaves would have been unpleasant for her to continuously wear.

As well, women who traveled with their husbands in war at the time were a mark of the man's status, and that he could afford to keep with him the luxuries of home (as.evidenced by what would later become known as the "Immortals" of Persia, who were known for being decked head to toe in gold and silks, and traveling with their wives, children, servants, and so forth while eating their own rations of luxury foods not afforded to the average soldier). So to have one's wife who travels with you as a mark of status dress constantly as a slave would be.... Well, weird.

So there's that. It's a lot to undertake, but what it's for will be entirely worth it.

Oh, and so this ties in with the "Age of Steam": let us remember that the Cyrus Cylinder was lost for centuries before it was re-discovered by an Assyro-British man named Hormuzd Rassam in March of 1879.

via Wikipedia

No comments:

Post a Comment